Term Papers (Hausarbeiten)

Steps of Academic Writing

The writing of an academic paper is not limited to the writing of the text itself. Both before and after this there are a number of important steps that must be taken into account when planning a paper.

Time-Management

It is advisable to work out a schedule for the paper before starting the writing process. Especially when it comes to the locating and review of relevant literature, this can often take more time than might be initially assumed. If the required books have been borrowed by someone else or even have to be ordered via interlibrary loan, it can take several weeks until they are available. The further steps also take time. And last but not least, there should be enough time at the end to proofread the work (or have it proofread).

An overall schedule can be helpful for the coordination of different assignments, for example during the semester breaks. It enables more effective use of the limited time available. In addition, a schedule can have motivating effects by showing the points already successfully completed during the course of writing a paper.

Papers are usually written during the semester break. Please bear in mind that during this time office hours are often offered at different times and/or less frequently, and lecturers may also be on holiday. If necessary, it is therefore best to arrange consultation appoint-ments at the end of the teaching period.

Finding a Topic and Formulating a Question

The first step in writing an academic paper is to find a topic. In so doing, it is not enough only to identify the issues which the paper will address. It is also necessary to formulate a question that makes it possible to work on the topic with an approach specific to religious studies. Developing a research question is certainly a demanding task. A good question does not usually stop at asking how things can be described (this usually results in a simple reproduction of one’s readings with no critical input), rather an academic question aims at explaining the facts or their consequences. An exception to this can be language-focused research, where the reading and representation of the material is a demanding task in itself.

A second challenge is to narrow down the subject. Topics such as “The History of Hinduism in India” or “The Religiosity of Muslim Youth in Germany” are simply too broad to be dealt with in the context of term papers or even a Bachelor’s thesis. The identification of a topic is also difficult because it requires basic knowledge of the subject in advance. Only then is it possible to determine the more concrete questions into which a topic can be broken down.

Therefore, finding the right topic cannot be done at the desk alone. It requires an initial, rough overview of the available literature and the state of research, as well as conversation with the lecturer. Do not hesitate to tell the lecturer your own ideas, but also be prepared to listen. If you have already acquired some basic knowledge, you can take up the lecturer’s suggestions and work them in sensibly.

Often you can start from a problem that you have encountered in a seminar or even outside the university. For your paper it is essential to make the problem manageable by formulating a clear question. It can be helpful to create a mind map on which you try to set out and structure different aspects of the topic. You only have to concentrate on one of these aspects - the more precise and narrow your question becomes, the easier it will be to work on it.

The definition of a ‘religious community’ is apparently controversial, as the debate on Scientology shows. The question “What is a religious community?” would be too broad to be answered in a term paper. Moreover, normative approaches - for instance “Why Scientology is not a religious community” - are inappropriate in academic papers. It would be possible to raise a question that picks out one of many aspects, namely the legal debate surrounding this issue: “Which argumentations are used in court decisions about the recognition of religious communities?” The title of the paper could then be: “Judicial argumentations in determining the status of ‘religious community’. An investigation into the example of Scientology.”

Outline and Selection of Literature

An initial outline can be established immediately after the research question has been formulated. This allows one to explicate the basic scheme of the work without getting lost in the details of the material. The outline is also the basis for the selection of literature. Only when the approximate direction of the research is known is it possible to then determine which literature is relevant. In addition to literature on the subject, it is often necessary to have an insight into the theoretical literature in order to provide a background for the research question. In a second part of the assignment, depending on the focus of the topic, students can analyse their own selection of sources.

The outline of your Scientology term paper might now look like this:

-

Introduction

-

(Descriptive part)

2.1 About Scientology

2.2 Overview of conflicts and court trials that have taken place

-

(Analytical part)

3.1 Analysis of documents and legal rulings

3.2 Reference to religious studies literature on Scientology

-

Conclusion

For more details, see the section on Outline of Chapters.

Literature Consultation and Reading

Sufficient time should be planned for the literature consultation. Relevant works may already be on loan or even have to be ordered via interlibrary loan. It is therefore advisable to acquire an overview of the required literature at an early stage. (For details of this process, see the section on Literature Consultation.) The range of inquiry is always the current state of research: the texts on a topic are not chosen arbitrarily, but should reflect the particular research area. Of course, it is not possible to reproduce the entire literature on a topic in one paper. However, the selected texts should always be embedded in a context: Which research area do they originate from? To which texts and/or authors do they refer? What other research areas are there that are not considered in the paper? A short overview of the state of research and the existing literature should therefore always be presented at the beginning of your text, for example after the introduction.

The actual work then follows with the reading and evaluation of the selected literature. Again, it is important not to rush into the literature without prior consideration. The reading should also be done with the research question in mind. What kind of argument does the author pursue? Does it agree with your own approaches? If not, can your own approach be justified or should you adapt your theses?

For more details see the sections on Literature Consultation and Reading Techniques.

Writing the Paper

Most of the work is done with the writing of the actual text of your assignment. However, if the previous steps have been thoroughly completed, the effort involved in the actual writing of the paper is reduced considerably. Ideally, one should have a clear question and a clear outline, know the literature and just need to get started. One should not only have the layout of the chapters in mind, but also the rough structure of the argument. In this way any weaknesses in structure will become apparent early on, and not only after the assignment has been written.

Write out a basic plan of your term paper, including the structure of your arguments. This will make it much easier to write. You can also include the literature to be used and/or any especially appropriate quotations.

After writing the text, you have to spend some time on post-processing. The text should at least be proofread for consistency of content and for any formal errors (spelling, grammar). It is helpful to have someone else proofread the text, because after having worked on it for some time, one becomes blind to many flaws and errors.

Appearance, i.e. a neat layout, is also part of an academic paper. Here, too, you can reduce subsequent work to a minimum if you work properly from the start. This includes creating an automatically generated table of contents and bibliography. For more details see the sections on Word Processing and Literature Administration.

Structure of a Paper

A term paper must meet certain formal criteria. In addition, there are a number of guidelines regarding the structure, which should be followed.

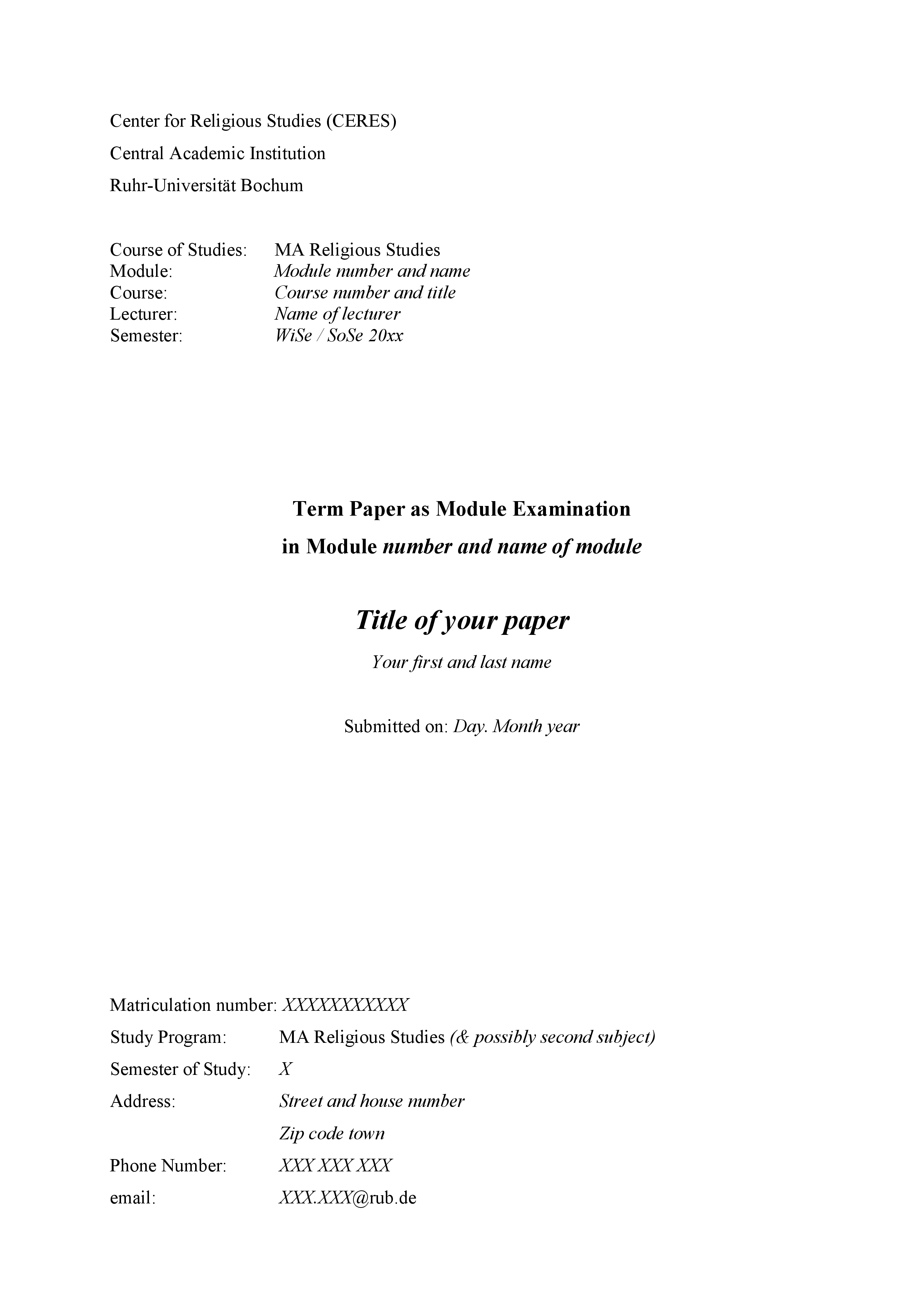

Cover Sheet

At the front of each term paper there must be a cover sheet containing several important pieces of information. The cover sheet should present this information as clearly as possible. It must contain:

-

Name of the university, faculty and subject of study

-

purpose of the paper (e.g. “Term Paper as Module Examination …” or “essay as examination for the module part …”)

-

title, course number and semester of the seminar/module as well as the names of the lecturers

-

title of the paper

-

name, matriculation number, combination of subjects, number of semesters, address, telephone number, and email address

-

date on which the work is submitted

The figure shows an example of a cover sheet.

Table of Contents

The table of contents contains the chapters and subchapters of the paper with page numbers. The table of contents itself should not be listed. Many word processing programs support the automatic creation of a table of contents. For more information, see the section on Word Processing.

Outline of Chapters

Each paper consists of an introduction, a main body and a conclusion. In the introduction the topic of the paper, the question and the structure of the paper are presented. Thus, the reader can already anticipate a certain structure and does not have to deduce it from the text. The main body then contains a sketch of the literature or the state of research and, as the most important part, the student’s actual work on the topic. Finally, the text is briefly summarized once again and the main findings are noted. The conclusion contains no new information or arguments.

However, this structure generally does not fully correspond to the outline of chapters. While the introduction is often called “Introduction”, and the conclusion is likely to be found under the heading “Conclusion” or similar, the main part usually consists of several chapters. The chapters of the main part should reflect the structure of the paper well and be named accordingly, so that the outline of the chapters already gives a good impression of the main topics. Sub-chapters can be divided into smaller sections, but the outline should not be too detailed. In practice, it is often best to divide the main section into three parts, but this is only a rule of thumb: the chapters and sub-chapters should not be unconnected but should be linked together in a meaningful way.

Decimal classification is suitable for the outline of chapters: chapters numbered with 1, 2, and so on, sub-chapters with 1.1, 1.2, etc. An outline level must never contain only a single chapter: If there is a chapter 2.1, then there must also be 2.2.

The individual parts should roughly follow the following structure:

-

Introduction to the topic, for example by linking it to historical or general debates

-

Presentation of the subsequent topic of the paper and, if applicable, reasons for the choice of topic

-

Limitation of the subject area: which aspect of the problem is relevant and can be treated meaningfully in the context of the paper, and which aspects must be left out?

-

Formulation of a research question or project, explication and justification (e.g., research gap, relevance for research in religious studies, etc.)

-

Description of the procedure and structure of the paper

-

Short overview of the literature used in the context of the state of research and possibly the sources

Imagine the introduction of a paper as being like a funnel: you start broadly, with a reference to a generally relevant issue, and then narrow it down to your chosen problem. This approach has its counterpart in the conclusion - here the findings of the paper are again opened up into a more general debate.

-

Presentation and execution of the preceding arguments, answering the question raised in the introduction.

-

Reproduce the researched and selected literature and discuss divergent approaches and arguments; do not retell the content, but select specific focal points based on the question posed.

-

Back up your statements with meaningful examples and quotations; pay attention to the corresponding citations in the footnotes.

-

Summarize the presentation and argumentation of the text briefly, and gather everything together in the formulation of a result that you have arrived at.

-

If necessary (especially in empirical work), critically reflect on your own approach: Was the method useful? Has anything remained open or unclear?

-

Concluding statement on the topic: significance of your own results - both for your specific question and for the general topic.

-

Outlook regarding further questions which your work could not answer or which your results have raised for further research.

The conclusion does not provide any new information that has not already been dealt with in the main part (citations are therefore generally no longer necessary here).

If you have written a neatly structured introduction, you can now “backtrack” the other way round - from the specifics of your work to the generalities of a larger debate. In any case, it is important that you refer to the introduction - in this way you make your work coherent and make it clear to the reader that you have written a well-structured and precise academic paper.

Bibliography and Appendices

At the end of the paper there should be a complete list of all literature used. The bibliography should not be filled up with literature that is not cited in the text. If a publication is important in terms of content, it should be cited, otherwise it does not have to be included in the bibliography. For the formatting of the bibliography see the section Citing Literature.

Papers that are rich in material can also contain one or more appendices, in which e.g. illustrations, source texts or similar can be placed. The appendices do not count for determining the length of the paper.

Formatting

A term paper in standard format usually contains about 12-18 pages or 5,000-7,000 words. However, the obligatory details are determined by the lecturers. The following guidelines apply to all papers:

-

font size 12pt

-

line spacing 1.25 to 1.5

-

Right margin 4cm - for notes and corrections; left margin 2cm, top/bottom 2-3cm

-

Detached headings with section numbers

-

Footnotes at the bottom of the page (no endnotes)

-

Page numbering from the second page onwards (the title page counts as page 1, but should not have a page number on it)

-

Text in justification with (automatic) hyphenation

For formatting a term paper with common word processing programs see section Word Processing.

Language

Good linguistic expression is also part of a successful paper. Contrary to common assumptions, language is not more academic if it uses many foreign words and complex sentences. The use of technical terms should make a text more precise and - for experts in the field, including the markers - more comprehensible, not less comprehensible. Above all, make sure that you yourself understand what you are writing.

Be precise and specify to whom you are referring, e.g. by saying: “The author considers that …”. Likewise, you should avoid the first person when you present facts or others’ theories; the first person is reserved for your own arguments or opinions.

Write in a clear way such that no more words could be deleted from your sentences. Filler words like “actually”, “quite”, “to a certain extent” or “ eventually” take away persuasive power from your arguments because they weaken their significance. It is better to write your work in such a way that all statements are fully intended as they are written there. If there are limitations to be considered, they should be made explicit and explained.

The argumentation of the work should also be reflected in the language: Causal links are an important means of connecting your arguments conclusively. However, a common mistake is to make causal links in places where they do not belong. Check very carefully whether sentences or parts of sentences that start with “therefore”, “nevertheless”, “in view of” or other phrases that refer to what has preceded them really do relate appropriately and clearly to what precedes.

Particularly with longer sentences, it is easy to come across incorrect grammatical constructions. Make sure that all formulations, connectors and relations are correct. It is also important to have correct and consistent orthography and punctuation.

For improved readability, the text should be structured with paragraphs. However, a new paragraph should be deliberately added when a new aspect is addressed. Putting each sentence in a separate paragraph is just as unhelpful as a text without paragraphs.

Marking Criteria for Term Papers

CERES lecturers follow a catalogue of criteria when marking written work. This will be made transparent in order to enable students to self-evaluate their written performance and to make the grading of their work comprehensible.

Generally, the work of the early phases of study should already try to follow this standard. However, these criteria are only applied in their entirety from the BA thesis onwards. The criteria are as follows:

– Quality of research – Expertise – Level of reflection – Consistency of argumentation – Judgement – Originality – Form

The evaluation of these criteria is best illustrated using binary positive/negative pairs as follows:

| positive | negative |

|---|---|

| A good overview of the state of literature can be detected. | Only little, partly or completely outdated literature was consulted. |

| Appropriate literature was selected according to transparent criteria and with reasonable judgement. | Important standard literature was ignored. |

| Only books were used, important articles are missing. | |

| Convenience appears to be the criterion for the selection of literature (important publications were ignored because of interlibrary loans or language barriers). | |

| The literature cited in the bibliography is taken up appropriately in the text. The literature is selected according to the requirements of the paper. | Large parts of the listed literature are not considered in the text. The literature is haphazardly selected and does not relate to the question. |

| The literature and its academic background are critically reflected. | Literature is adopted uncritically; non-academic literature is used as a source without being classified accordingly. |

| Competent handling of terms and concepts. | Relevant concepts/ terms were not properly understood. |

| Connections were correctly identified, cross-connections were drawn. | Putting the topic under discussion into a larger context is too vague or wrong. |

| Paper contains incorrect factual information. | |

| The paper is theoretically well thought out. | No research question or issue or methodological-theoretical reflection recognizable. |

| Key metalinguistic terms were defined, historically situated and tested for their suitability. | Terms that are crucial for theory formation were used without reflection. |

| The individual stages of analysis were made transparent through methodological reflections. | Methodological reflection was absent or insufficient. |

| Lack of differentiation, generalising statements (“Christians are …”, “Hindus believe …”). | |

| Positioning of one’s own work within current discourse around the subject. | Ignoring secondary literature on religious studies; developing questions that have nothing to do with religious studies. |

| Distinguishing between insider and outsider perspective. | Arguing or even evaluating and judging from an insider perspective. |

| Analytic description | Normative assessments |

| Contextualize the concept of religion (Which culture/time/space am I dealing with right now? How can religion be identified there?) | Using the concept of religion without reflection. |

| Reflecting the discursive power of academic speech about religion. | Taking the existence of religion for granted. |

| The question is clearly formulated. It refers to the chosen topic and can be worked on within the framework of the paper. | No question has been formulated. The question is too broad or too narrow. |

| Coherent line of thought. The argumentation refers to the selected question. | Argumentation is logically incoherent. |

| The topic was lost sight of; question and conclusion do not fit together. | |

| Method and research question are matched to each other; the chosen method allows a result in keeping with the research question. | The method was not chosen to suit the question. |

| The method was not adequately reflected. | |

| The method was applied in a sensible and technically correct manner. | The implementation has methodological shortcomings; no explicit method is apparent. |

| Different views (e.g. from the academic secondary literature) are considered and weighed against each other. | Crucial elements of argumentation are insufficiently supported; alternative views were ignored or not problematized. |

| The result was presented thoughtfully and appropriately with regard to the research method. | Question and result are not in accordance with the basis of the research (e.g. too broad conclusions are drawn from much too little research). |

| A creative question or solution is developed. The paper reflects individual thoughts on the topic. The conclusion illustrates the autonomy of the work. | No or hardly any individual thoughts are recognizable. |

| Stealing ideas is the worst of all sins!! Copied or downloaded papers, which are submitted or presented as a student’s own assignment, are without exception graded as 6. | |

| The paper is formally correct. | Too many spelling, grammar or punctuation mistakes (more than 3 per page). |

| Statements are not backed up, cannot be verified. | |

| Bibliography inconsistent, unsystematic or missing. | |

| Quotations are formally incorrect (e.g., miscopied, missing or incomplete bibliography). | |

| Paper is too long or too short. |

Early consultation with the lecturer about a possible term paper is absolutely necessary. The topic should be approved, a deadline set and, possibly, the formalities agreed upon. Depending on the lecturer, suggested literature will be supplied to help you get started.

- Do I have a well-defined topic with a concrete question?

- Is the structure of my paper logical, comprehensible and appropriate to the question?

- Have I consulted the lecturer about my topic?

- Are the findings of my literature consultation academic literature?

- Have I found all literature relevant to the question and the topic?

- Have I taken into account the given formalities?

- Which citation style do I use and have I cited consistently?

- Did I create a bibliography?

- Have I proofread the assignment and had it proofread?

Plagiarism

In the field of academia - in which you are also involved as a student - it is no longer a trivial offence to pass off someone else’s intellectual property as your own thoughts. Plagiarism is now severely punished at all universities. At the Ruhr-Universität Bochum the following applies: Not only are all papers in which plagiarism can be found considered “insufficient”, but plagiarism must also be reported to the examination office and thus to the legal department. The latter can initiate punitive administrative proceedings to impose fines and, in serious cases, result in exclusion from university.

In the academic world, plagiarism includes various offences: submitting a work that someone else has written for the student (ghostwriting) or submitting someone else’s work under one’s own name (full plagiarism), taking text from other works - or from the Internet - without citation (partial plagiarism) or submitting one’s own work several times on different occasions (self-plagiarism).

It is therefore also extremely important to correctly cite and substantiate any passages from other works - without adequate citation, even adapted and possibly slightly modified paraphrases from the works of other authors become plagiarism.

It is also important for the marking of your work that you clearly mark which ideas you have taken from another work and which are your own analysis or conclusions. Your personal contribution is an important part of a paper, so you are not doing yourself any favors if you leave the marker unsure about what your personal contribution is.

If you indirectly quote the argument of another author over longer stretches, you should make this clear by using the subjunctive in addition to the use of clearly indicated evidence. You can emphasize your part in the work by using clear formulations at the important points (“I have shown that …”; “One can now conclude that …”).