How to Deal with Literature

Literature Consultation

The literature consultation for a paper, a presentation or any other work is an important part of the assignment. Therefore, this research should be carried out on one’s own. Finding, viewing and evaluating the available literature is an important skill acquired during the course of study. However, after you have conducted an initial survey, you can (and should) discuss your findings with the lecturer. In this way you also avoid reading too many texts that you cannot use in the end.

When researching the literature, it is important to avoid two common problems: First, it is easy to find too much literature. On the other hand, there is also the danger of not finding important texts that may not immediately catch the eye. It is therefore important to start the search from different places in order to find not necessarily a lot of literature, but appropriate literature. There is not a single catalog where you can find all the relevant literature, so it is important to know the different search methods.

There are two possible strategies for finding literature, which can also be combined:

Top-down research starts with general overviews: for example, subject-specific bibliographies (you can often find corresponding bibliographies on the websites of individual institutes) or encyclopedias. There you will get an overview of the basic literature relevant to a given subject, such that you are less likely to overlook something important. For more specific literature, however, you need other sources.

The bottom-up strategy starts with the texts already known to you (from courses or through previous research). The bibliographies of monographs, essays and articles can then serve as a starting point for further research. This makes it possible to obtain a broad overview of a specific topic. The author’s expertise is used to distinguish relevant from less relevant literature. Qualification papers in particular (such as dissertations) usually provide a good overview of the state of research on a topic. In addition, one can find important literature that might not otherwise have been found by a free search in the library catalog.

Encyclopedias

A first good introduction to finding literature is provided by encyclopedias relevant to religious studies. The articles offer a brief overview of a topic, and they usually contain a series of relevant bibliographical references at the end of the article. These can be used for a more detailed study.

Please note, however, that a paper should never be based solely on encyclopedia articles. In addition, some of the encyclopedias (or the individual volumes) are older, so you cannot rely on finding up-to-date references there. Some reliable encyclopedias for religious studies are:

-

The Oxford Handbook of the Study of Religion, ed. by Michael Stausberg, Steven Engler, Oxford 2016.

-

The Routledge Handbook of Research Methods in the Study of Religion, ed. by Michael Stausberg, Steven Engler, London 2011.

-

The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion, second edition, ed. by John R. Hinnels, London/New York 2010.

-

The Encyclopedia of Religion, 16 Volumes, ed. by Mircea Eliade, New York/London 1987.

-

The Encyclopaedia of Islam, 12 Volumes, second edition, ed. by P.J. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs, Leiden 1860-2004.

-

Encyclopaedia Judaica, 22 Volumes, second edition, ed. by Fred Skolnik, Detroit 2007.

In German:

-

Handbuch religionswissenschaftlicher Grundbegriffe, 5 Bände, hrsg. von Hubert Cancik, Burkhard Gladigow und Karl Heinz Kohl, Stuttgart 1988–2002.

-

Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Handwörterbuch für Theologie und Religionswissenschaft, 8 Bände, vierte Aufl. hrsg. von Hans Dieter Betz u.a., Tübingen 2000–2005.

-

Metzler Lexikon Religion: Gegenwart – Alltag – Medien, 3 Bände, hrsg. von Christoph Auffarth, Stuttgart u.a. 1999–2000.

-

Theologische Realenzyklopädie, in Gemeinschaft mit Horst Robert Balz et al. hrsg. von Gerhard Krause und Gerhard Müller, 36 Bände, Berlin/New York 1977–2004.

-

Der neue Pauly. Enzyklopädie der Antike, 15 Bände, hrsg. von Hubert Cancik, HelmuthSchneider und Manfred Landfester, Stuttgart 1966 ff.

-

Historisches Wörterbuch der Philosophie, völlig neubearb. Ausg. des »Wörterbuchs der philosophischen Begriffe« von Rudolf Eisler, unter Mitw. von mehr als 800 Fachgelehrten in Verbindung mit Günther Bien u.a. hrsg. von Joachim Ritter und Karlfried Gründer, 12 Bände, Darmstadt 1971–2004.

Library Catalogs

The library catalogs are a good place to look for monographs in particular. The catalog of the Ruhr-Universität can be reached at http://www.ub.rub.de/.

However, not all books are available in the University Library. Therefore, it is worthwhile to search the catalogs of the library associations and to order books via inter-library loan if necessary. The university libraries in North Rhine-Westphalia have joined together to form HBZ (http://www.hbz-nrw.de/ in German). The catalog KatalogPLUS on the page of the RUB library (http://www.ub.rub.de/) allows you to search in various libraries.

Library catalogs are generally not suitable for finding articles in anthologies or journals. Accordingly, a literature search should not be limited to the library catalog alone.

Tips for research

-

In library catalogs you usually search for literature by keywords. Remember to find synonyms for your topic and possibly try keywords in different languages. Your topic can be very specific; consider under which keywords you might find publications that deal with this topic (for example, if you are looking for literature on the definition of religious communities, you will not necessarily find a book with the same title - in an “Introduction to the Sociology of Religion”, on the other hand, you will certainly find something).

-

Library catalogs themselves also work with keywords. These can be found in the details of a book. Perhaps one of them fits your topic well - you can find out with a simple click which books the library staff have marked with this keyword. The advantage of this is that you don’t have to rely on your search term appearing in the title of a book - the keywords can also cover general topics or content.

-

Have you found a current dissertation or habilitation thesis on the topic? Lucky hit! Because these theses usually contain a detailed state of research on their topic themselves, which should include all relevant publications.

-

If you have found a relevant book, you should also look to the right and left of it on the shelf. As a rule, thematically related books are grouped together, so that you can find books here that you might not have found in the catalog.

-

Be sure to take part in an introduction to the university library and library catalogs at the beginning of your studies. These guided tours are usually free of charge and regularly offered by library staff.

Literature Databases

Literature databases are a suitable means of obtaining information on individual articles. An overview of the literature databases to which the RUB offers access can be found at http://www.ub.ruhr-uni-bochum.de/DigiBib/Datenbank/Gesamt.htm. The databases ATLA, Philosopher’s Index and Sociological Abstracts are of particular interest for the study of religions.

Some literature databases offer the possibility to directly access the online holdings of journals. This is, of course, very convenient, as it saves you the trouble of searching for the journal, copying it or even an inter-library loan. However, it should not be the criterion for literature selection whether a journal is available online.

Some literature databases can only be accessed from the RUB campus network. It is therefore best to carry out your research from a campus computer or connect to the university network from outside via VPN. You can find instructions for this at http://www.ub.ruhr-uni-bochum.de/DigiBib/zugang-extern.html.en.

Online Sources

There is also the possibility of an internet research. However, please make sure to apply the same standards of quality to online sources as you would to printed works. Some internet services offer a convenient way to find literature, similar to literature databases, for example Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.de/).

However, a number of internet-based sources are not suitable for academic use. This includes, above all, Wikipedia. In an academic work you should not quote Wikipedia! Many Internet sites are also more likely to be the subject of academic research than a source. This largely applies to the online output of religious communities.

Comprehensive search: DigiBib

With the DigiBib of the HBZ (http://www.digibib.net/) a search option is available, which can search several of the mentioned sources simultaneously. Library catalogs, journal article databases and electronic full texts are searched. A search in the DigiBib thus already covers some of the above-mentioned search options under a uniform search interface. This makes the DigiBib a good starting point for a comprehensive literature search. Other sources should nevertheless be considered.

If you document your search process, you may save yourself some work. Note down the search keywords you have used and make a list of all books found and considered in the catalog. On this list you should note which book was unexpectedly useless, which was perhaps out of place, and which still needs to be acquired. In this way you can save yourself going back to the shelf for a new search and expand the pool of already searched keywords in the case of an in-depth search.

Reading and Understanding Literature

How to Organize Literature

An important skill that you will need to learn during your studies is the skillful handling of large amounts of academic literature and a quick and reliable assessment of its utility for your needs. This is also a matter of practice; however, we would like to give you some tips at this point:

-

You can already see from the cover and/or the table of contents what the aim of the book is: is it a research study or a teaching book; does it provide an overview or does it go into a topic in depth?

-

A basic rule: not everything that can be found in university libraries is of high academic quality. Here you will find both publications of popular science as well as normative publications of a specific publisher. Always critically examine the premises, style and argumentation of a work.

-

Who is the author of the selected work? From what discipline or school are they from? What else have they published and what are their main areas of work?

-

When is the publication date? Is it sufficiently current for the topic? Does it possibly originate from a context/era that might affect its arguments (e.g. colonialism, National Socialism)?

-

In which series or publishing house did the publication appear or in which journal did the article appear? What does this series/ this publishing house/ this journal stand for? Who is the editor?

-

How detailed, up-to-date and academic is the bibliography? To which disciplines does the author refer?

Reading Techniques

Not only writing but also reading academic texts must be practiced. Depending on your interests and requirements, different forms of reading can be applied. Before reading, one should therefore consider what goals are associated with reading a text. This determines the general conditions of the reading:

-

Is the text course literature, the basis for a paper or exam content?

-

Is the text only of interest due certain of its contents, or is it a general overview?

-

What previous knowledge on the topic of the text is already available?

-

How much time can be spent on reading?

Analytical Reading

The most important reading method is analytical reading. The aim is to understand all central concepts of a text and to work out the theses and trains of thought. A critical approach to the text should be taken, and both successful aspects and weaknesses should be uncovered. The so-called PQ4R formula can be helpful in this process:

-

Preview: First overview of the text

-

Question: Formulate questions directed to the text

-

Read: Read the text

-

Reflect: Reflect upon the contents and their context

-

Recite: Reproduce the content (e.g. in form of a summary)

-

Review: Review of your own reading

When reading the text, it is useful to work with markings and notes in the margins. In this way, important and unimportant things are distinguished from each other while reading and the content can be more easily absorbed. It also makes it easier to re-read the text at a later time. Three forms of annotation can be distinguished:

-

Marking: Either marking with a highlighter or underlining with pencil or crayon. You can also use different colors for different meanings, e.g. red=important, black=“Terms and definitions”, etc.

-

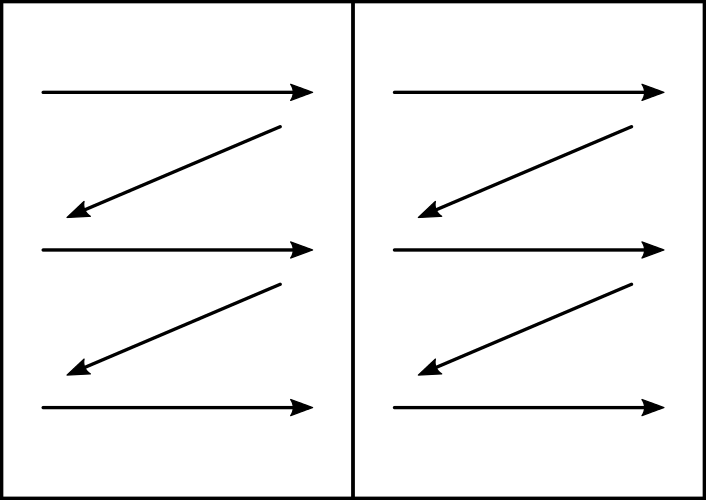

Non-linguistic annotations: Small symbols can be used to characterize text passages. This can be done directly in the text or in the margin. See the table below for examples.

-

Linguistic notes: Short remarks and notes on the contents of a paragraph can be noted directly in the margin. More detailed thoughts can also be noted on the back of the text.

Markings and annotations should of course only be made on texts that belong to you personally, not in borrowed books. It therefore makes sense to either make annotations in the digital version of a text, for example on a tablet, or to work with copies or printouts. Reading on a laptop/PC is also possible, but it is often more difficult to cognitively process what has been read.

| Structure category | Related question/explanation | Note in the margin |

|---|---|---|

| Topic/Subject | What is it about in general? | Topic |

| Focus | What is it about in particular? | Focus |

| Research question | What should be found out? | RQ |

| Definition | How exactly are key terms understood? | Def. |

| Aim | What is the aim of the text? What does it want to find out, show, question or similar? | Aim |

| Theses | What is/are the proposed answer(s) to the research question? | T or T1, T2, … |

| Data basis | What material is being used? What material is the research question aimed at and from what are theses derived? | Data |

| Method/theory | Which perspective and which “tool” does the text use to approach the topic? How and on what intellectual basis is the question answered? | M/T |

| State of research | What academic literature has been published on the topic or the specific focus to date that the text builds on? | SoR |

| Announced procedure | How does the text proceed in detail? What steps does the text take in its course? | Procedure |

| Core statements | What are the central statements of the text? | • |

| Enumeration | Where does the text mention several points that are dealt with one after the other? Especially implicit enumerations. | 1./2./3./… |

| Particularly relevant | What else is particularly relevant for me, my project, my own question or my personal interest? | ! |

| Unclear | Which terms are unclear to me? Which statements can I not understand? | ? |

| Contradiction | Which statements do I disagree with? | X |

Table: Structural categories for marginal notes. Source: Partly taken and translated from Roers, Benjamin. 2020. “Geschichte und Gegenwart meiner Notizen”. tub.torials (blog). 10 December 2020. https://www.tub.tuhh.de/tubtorials/2020/12/11/vergangenheit-und-gegenwart-meiner-notizen/ under the licence CC BY 4.0. Own adaptations.

»Skim Reading«

In order to gain an overview of the core contents of a text in a short time, there are various reading strategies:

- Selective reading: With selective reading only parts of the text are read. The sections to be read are selected in such a way that the central information can be captured as far as possible. If necessary, additional sections can then be consulted. The following procedure can be used for guidance:

-

First, look at the table of contents, if available. If there is no table of contents (e.g. for articles), the subheadings can be consulted. In this way it can be seen how the author has arranged the topic and which sections of the text are relevant for your own work.

-

Read the introduction or the first section to get an overview of the question.

-

The main part of the text is skipped and instead the conclusion is read directly. This can be directly related to the questions raised in the introduction to see what the author concludes.

-

Depending upon own question and interests, now further sections from the main part can be read, in order to reconstruct the argument in detail.

If you have a specific focus in terms of content or methodology, for example in relation to a paper or a presentation, the text can be read from a certain angle and irrelevant passages can be omitted. It can be helpful to cross out passages that are not thematically relevant with a pencil. An important additional source of assistance is the keyword index, if available.

-

Searching reading: This type of reading aims to read a text as quickly as possible and still obtain important information. You should be clear beforehand which words or terms you want to find. The text is then searched for them and, if the terms do not occur, it need not be consulted further.

-

Cursory reading: Also a fast method. As with the searching method, more precise details are neglected. The point is to grasp the broader context and meaning of a text. As a result of this reading process, it should be clear which questions are addressed in the text. With this technique, the eyes only scan the text, not reading line by line. It is recommended to write down one or two key points per page.

After having read the text, try again to visualize the “blueprint” of the text: Where does it begin, where does it go from there, etc.? Formulate the core thesis for yourself once again. If this works, you have a reasonably good grasp of the text.

For optimal preparation for a course assignment or analysis of a text, you should follow up with a critical discussion after reading. This can be undertaken as textual criticism: Is the structure coherent? Are the premises taken up again later? Is the argumentation finished? (Sensitizing yourself to this can be doubly helpful - such things also play a decisive role in the marking of your papers). Meanwhile, courses often specifically ask for objective criticism of the text: are the premises of the text acceptable? Is the evidence conclusive? What is the method, if any? Are moral judgements made?

Summaries

In order to secure what you have learned on a long-term basis, it makes sense to write summary of important texts after reading them. On the basis of your markings and comments, it is easy to see which passages were felt to be important during reading. In the summary, these passages are briefly written out in your own words. This summary is a very valuable tool for working out the line of argumentation of a text and, if necessary, for detecting weaknesses in its arguments. You can also make notes regarding your own impressions, agreements and disagreements with individual passages. If the text has to be referred to at a later date, the summary can be used to visualize it very quickly. It is therefore recommended that you always prepare a short summary of any text you have read, to which you can refer if necessary. In order to be able to find the summary of a given text quickly, it is therefore advisable to store the summaries with the bibliographic data in a database. For more details see the section on Literature Administration.

For the summary you can use the following questions as a guide:

-

What is the topic of the text?

-

What is the author’s main question?

-

What is the author’s thesis in relation to that question?

-

What is the author’s argumentation structure?

A good summary captures in brief the principal content of the text. It is not a matter of identifying the most important sentences in the text and copying them into your own document, but of reformulating the contents into larger main ideas. This is the only way to really make the text your own and integrate it into your own learning. Depending on the structure of the text, a graphic rendering of its statements as a diagram can also be helpful.